Professor Shatzmiller speaks with CTV News about Morocco losing thousands of people and a major part of its history to the earthquake

By

In the aftermath of a deadly earthquake, Moroccans are trying to grapple with the deaths of thousands of people amid widespread destruction that left some sites crucial to human history in ruins.

Western University of Ontario historian Maya Shatzmiller, who specializes in Marrakech, one of the areas hit hardest by the earthquake, said a United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) world heritage site dating back to the 12th Century has been damaged and another site has been destroyed.

"One of them, a mosque in the mountains, has completely been destroyed," Shatzmiller told CTVNews.ca in an interview Tuesday. "The other one, a major mosque in Marrakech itself that was under reconstruction at the time when this quake struck has been also damaged."

The Koutoubiyya mosque in Marrakesh is an "essential monument" of Muslim architecture and an important landmark in the city, UNESCO says on its website.

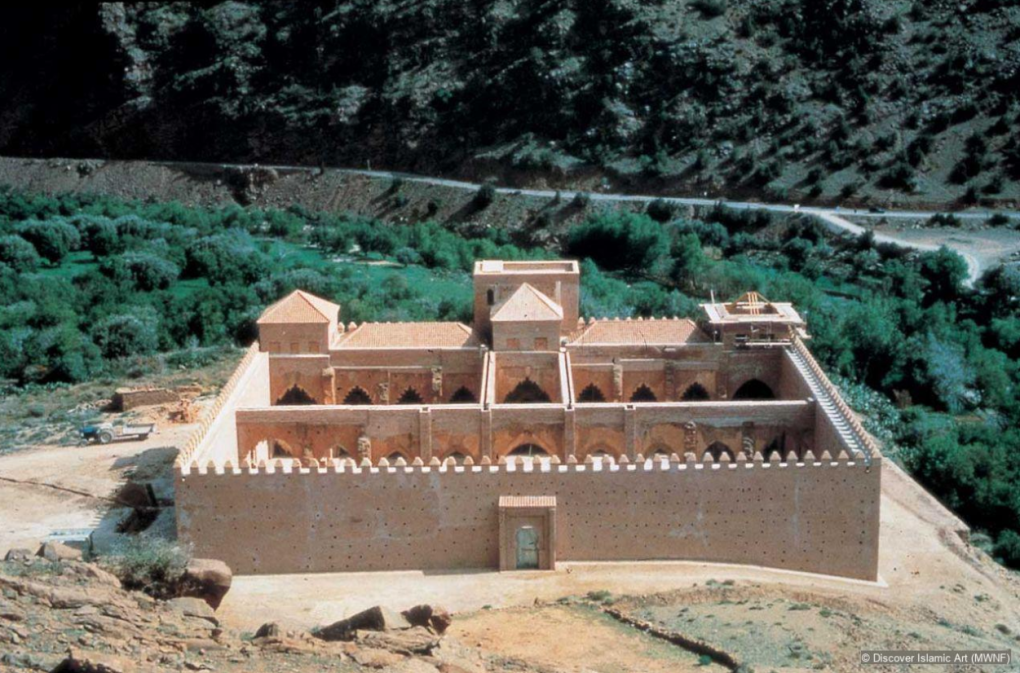

Another important mosque on UNESCO's list of sites is the Almohad mosque of Tinmel located in the Atlas region where the earthquake struck. It is the birthplace of the Almohad movement, from where its leader launched his conquest of North Africa and was later buried in 1130 AD, according to the Museum With No Frontiers.

Koutoubiyya mosque in Marrakesh. (Yvon Fruneau/Copyright: © UNESCO)

These sites are not only important for the people of Morocco but were also well-preserved mosques showing how Indigenous Africans interacted with Arab conquerors, Shatzmiller said. The country, she said, is incredibly unique because of the ruling dynasty, the Almohads, during the time the mosques were constructed.

The dynasty's rule spread over much of northern Africa and Spain while also having ties with the Arab world and Indigenous Africans known as Berbers.

"The dynasty is also important because it highlights another component of the Moroccan nation that I would say is not very well articulated, which is the Berbers component," Shatzmiller said.

Today, Berbers make up a large portion of Morocco's population, she said. The buildings contained manuscripts, books and historical artifacts that were some of the best-preserved stories about the Almohads and Berbers.

Almohad mosque of Tinmel in Atlas region. (Museum With No Frontiers)

"This is a very unique dynasty in many respects," Shatzmiller said. "Their centre was Marrakech, which has been now really decimated by this event, and destroyed many of these monuments that were standing."

The 6.8 magnitude earthquake hit the Atlas region on Friday evening, shaking the city of Marrakech about 70 kilometres north and the surrounding area.

It was the most powerful earthquake felt there in more than a century, but not the first.

In 2004 an earthquake in the northern Rif region killed more than 600 people. Decades prior in 1960, the Agadir region was the epicentre of the country's deadliest earthquake that killed at least 12,000 people.

An estimated 60 to 90 per cent of the residences and structures were lost or severely damaged from the disaster that hit Agadir, according to the faculty of social studies at the University of Sherbrooke, in Quebec.

"Earthquakes in the magnitude 6 range are more common in the northern part of Morocco near the Mediterranean Sea, where a magnitude 6.4 earthquake struck in February 2004 and a magnitude 6.3 in January 2016," the United States Geological Survey said.

Shatzmiller, who has written numerous books on Morocco and Marrakech, said the destruction last week will have lasting impacts.

"This is the evidence that they have, and when it disappears like this, it's an endless disaster that cannot very easily be remedied," she said.

WHAT MARRAKESH WAS LIKE BEFORE THE QUAKE

Shatzmiller said she felt like a piece of her heart was taken when she heard about the earthquake on Saturday morning.

"I immediately called my friends…and people were just heartbroken," she said. "The friend I spoke with, the local historian, he says, 'It was a terrible night. We were all outside. We didn't know what to think everybody was taken by surprise and shock.'"

Knowing the area intimately, Shatzmiller was not only concerned for the safety of the people but the culturally significant architecture that dates back thousands of years.

"The walls of Moroccan cities are like no other walls in the world," she said. "If you look at the pictures of the walls, they're very unique structures…If you look into it you feel that you are in a world of its own nature."

Medina of Marrakesh. (Philippe Garnier/Copyright: © CRA-terre)

Much of the older part of Marrakech and other cities are enclosed in walls that resemble a fort. Shatzmiller said the walls were similar to what Muslim Spain looked like before they were destroyed during the Crusades.

The mosque at the heart of the city was spacious, Shatzmiller said and contained centuries-old books that are now likely to be severely damaged.

"Marrakech in this particular environment has a special atmosphere, that intellectual place of the 12th Century," she said. "Let's see how they managed to salvage whatever can be salvaged. But it's absolutely a unique and special environment, both physically and mentally."