Making Nianhua

Nianhua offer numerous opportunities for learning about Chinese culture, but learning from nianhua first requires understanding that they are a form of print, and that even with marginal literacy rural Chinese society still had a tradition of using print to understand and explain the world in which they lived. Having access to that printed record is thus critical to our understanding of that society. Before beginning to read that record, however, it would be wise to follow Robert Hegel's suggestion that if one really wishes to understand a printed document, they must consider how an article of print delivered its message before asking what that message meant.

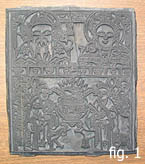

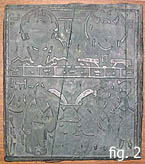

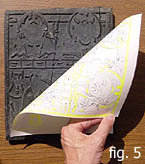

Nianhua were, and in some cases still are produced through xylography, or woodblock printing. The process of colour xylography begins with an ordinary line drawing pasted onto a block of hardwood. The artisan then cuts away the surface of the wood, leaving only the lines of the picture standing out in relief (fig. 1). An impression of that block is then taken and pasted onto another block where the surface is again cut away, this time leaving only those sections of the image that represent a particular colour in the finished print (fig. 2). That process is completed for each of the colours to be applied to the final picture. The image is then ready to be printed by applying ink to the surface of the outline block, and then pressing a sheet of paper onto the surface to receive the impression (fig. 3, fig. 4). This is repeated for each of the colours (fig. 5, fig. 6) and after a bit of manual touching up, the print is finished. Working in this fashion a well-organized printer could produce up to 600 prints a day, obtaining tens of thousands of prints from this set of blocks before they needed to be renewed. In a village the size of Yangjiabu, with about 200 families in the early 20th century, the combined output of the village is thought to have reached as high as ten million or more prints annually.

Although nianhua were found everywhere in China, the industry was dominated by a small number of mass producing specialists. Particularly well known in the early twentieth century nianhua industry were Yangjiabu in the eastern province of Shandong, as well as Yangliuqing and Wuqiang in the northern province of Hebei, Zhuxianzhan in the central province of Henan, and Mianzhu in the western province of Sichuan. Urban centres of production could be found in Taohuawu - a district of Suzhou, and in metropolitan Shanghai.III During their prime in the late 19th/early 20th century each of these industries marketed their products over extensive inter-provincial regions during the last months of the year. As the New Year approached the nianhua would be eagerly sought out and used to decorate homes and perform essential family rituals.

Questions:

-

What influence would the method of production have on the final appearance of the nianhua?

-

How is it possible that one small village, such as Yangjiabu, could produce as many as ten million pictures a year using only simple tools? What does this tell us about the social organization of the village?

-

What influence might the mass production of nianhua have on the community that purchased these pictures for use in their homes?

-

How would the timing of production influence the content of the nianhua?