The Nianhua Gallery

Honour, Wealth and Glory

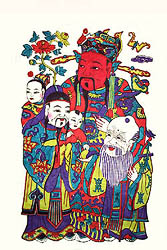

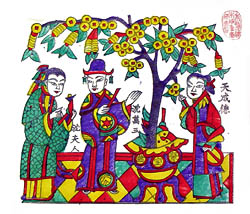

Good Fortune, Official Salary, and Longevity represent the ingredients of a happy life, and are represented in popular culture by a trinity of star gods. Fortune often appears holding a baby boy - male heirs being a great blessing and a sure sign that fortune smiled upon the family. Official Salary stands tallest with his official cap and tablet of office, and Longevity takes the form of an elderly immortal with an extended forehead and a peach of longevity (these attributes may also be perceived as symbols of fertility).

Fortune and Longevity have a more or less universal appeal and most cultures honour them in some way. The logic of 'Official Salary', however, may not be so apparent to readers not familiar with Chinese history. To understand why this attainment was so highly valued one must understand that the late-imperial Chinese state had created a system in which social prestige was closely linked to the civil service. There were many ways to become wealthy, but unless one had an official posting or title they would never be truly 'rich'.

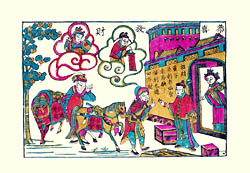

Scholarship was thus highly regarded, and the figure of the successful scholar was widely celebrated. As elsewhere, scholarly achievement was measured in degrees, and among these degrees it was the highest jinshi, or 'metropolitan' degree that was most coveted. The scholar who finished first in that category was given the title of zhuangyuan or 'optimus'. Nianhua often depict the triumphant scholar returning home after having won this honour through the state civil service examinations. The scholar's family and locality have good reason to celebrate, since it was expected that the benefits of officialdom would ultimately return to them not just in terms of prestige, but also in terms of political influence and remittances drawn from the scholar-official's substantial earnings.

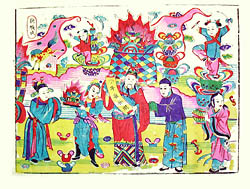

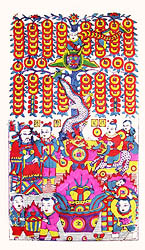

The value placed on scholarship should not cloud the fact that raw material wealth also had its attractions. The God of Wealth was a central deity in the Chinese pantheon, and nianhua of the late 19th and early 20th century abound with representations of gleaming jewels and precious metals. More subtle references to wealth are also suggested by rebuses (visual puns) such as a fish, which in spoken Chinese sounds like 'surplus'.

'Happiness and Wealth' Fengxiang, Shaanxi

'Money Tree' Mianzhu, Sichuan

'Fortune, Official Salary, Longevity' Yangjiabu, Shandong

'Fortune, Official Salary, Longevity' Yangjiabu, Shandong

'The Pot of Wealth' Yangjiabu, Shandong

'Republican God of Wealth' Yangjiabu, Shandong

'The Pot of Wealth' Yangjiabu, Shandong

'Money Tree' Yangjiabu, Shandong

'Wealth Comes to the Home by Five Roads' Yangjiabu, Shandong

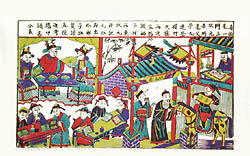

'Three Zhuangyuan in One Home' Yangjiabu Shandong

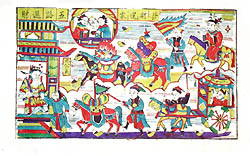

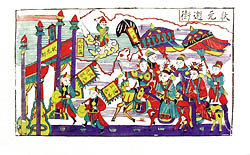

'Parade of the Zhuangyuan' Yangjiabu, Shandong

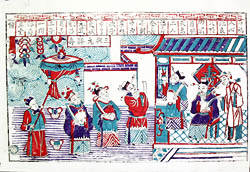

'Three Zhuangyuan' Yangjiabu, Shandong

'Martial God of Wealth (Guandi)' Yangjiabu, Shandong

'Shen Wansan' Yangjiabu, Shandong

'God of Wealth Comes to the Door' Yangjiabu, Shandong

'Fortune, Official Salary, Longevity' Zhuxianzhen, Henan

'Money Tree and Shen Wansan' Zhuxianzhen, Henan